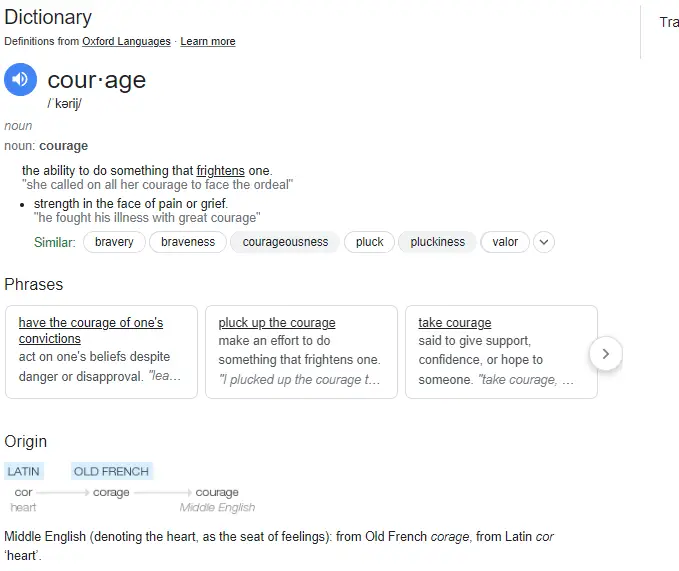

The Latin origin of the word courage (spelled “cor”) simply means HEART.

Not only does courage mean to do what you’re afraid of or to have strength when feeling pain.

Courage means to DO the right thing, regardless of if you’re afraid or it hurts.

Even if it hurts AND you’re terrified of the thing, courage says to do it anyways, because it’s right.

I contest that courage is a noun (person, place, or thing).

Courage is a verb (action, state, or occurrence).

Courage is not something you HAVE.

Courage is something you DO.

- You DO courage.

- You don’t have courage.

In order to do courage, you just do what you know in your heart is the right thing to do.

If what is right, just, and true, then there is no FORCE in creation that has the power to stop you!

- What Is Justice?

- How Does Jesus Define Justice?

- What Is A Right?

- Where Do Rights Come From?

- What Do You Have The Right To Do?

- What Do You ‘Not’ Have The Right To Do?

- What Is Truth?

- How Do You Know It’s The Truth?

- What Is Heart?

- How Does Scripture Define Heart?

- What’s Bob Proctor’s Explanation Of Heart?

- How Do You Deal With Someone Who’s Not Interested In The Truth?

- Is The U.S. Court System A Reasonable Way For Dealing With Those Who Are Not Interested In The Truth?

What Is Justice?

“Justice” is a complex and multifaceted concept that has been the subject of philosophical, legal, and ethical discussions for centuries.

It generally refers to the principle of fairness, righteousness, and moral rightness in the treatment of individuals and the allocation of resources and punishment.

Justice can be viewed from various perspectives:

Philosophical Perspective

- Moral Justice: Involves the idea of moral rightness based on ethics, rationality, law, natural law, religion, fairness, or equity.

- Distributive Justice: Concerns the nature of a socially just allocation of resources. It’s about fairness in what people receive, from wealth to social status.

- Restorative Justice: Focuses on repairing the harm caused by criminal behavior. It’s about the restoration of relationships, including victim, offender, and community.

Legal Perspective

- Legal Justice: Pertains to the application and administration of laws. It involves ensuring that laws are justly and consistently applied and enforced, and that legal processes are fair and impartial.

- Criminal Justice: Relates to how a society responds to criminal behavior. It involves law enforcement, court proceedings, and corrections.

- Social Justice: Concerns the fair and just relationship between the individual and society. This encompasses a wide range of issues such as equality, human rights, and discrimination.

Social and Ethical Perspective

- Equality and Equity: Involves treating people fairly and equitably, but not necessarily equally, as different people may have different needs and circumstances.

- Human Rights: Concerns the basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled.

- Fair Treatment: Ensures that individuals or groups are not discriminated against or oppressed by others.

Practical Applications

- In Courts and Legal Systems: Justice is the guiding principle in procedures and decision-making, aiming to ensure fair trials, proportionate punishments, and equal treatment under the law.

- In Society and Politics: It involves creating a fair and equitable society where rights are respected and protected, and resources are distributed fairly.

Justice is a foundational concept that underpins the functioning of legal systems, guides ethical behavior, and influences social policies.

It is not a static concept but evolves with society, reflecting changing values, norms, and understandings of what is fair and right.

How Does Jesus Define Justice?

Jesus’ teachings on justice, as presented in the Christian New Testament, emphasize compassion, mercy, fairness, and the love of God and neighbor.

His definition of justice goes beyond legalistic interpretations and focuses on the spirit of the law, the dignity of individuals, and the needs of the marginalized and oppressed.

Here are some key aspects of how Jesus’ teachings relate to the concept of justice:

- Love and Compassion: Jesus summarized the law as love for God and love for one’s neighbor (Matthew 22:37-40). This love is active and seeks the well-being of others, which is a foundational aspect of justice.

- The Golden Rule: Jesus taught, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (Matthew 7:12). This principle of treating others as one wishes to be treated oneself embodies a form of justice based on empathy and respect for others.

- Concern for the Marginalized: Jesus’ ministry focused significantly on the poor, the sick, and the marginalized. He advocated for the care and inclusion of those often neglected or oppressed by society, embodying a justice that uplifts the vulnerable (Matthew 25:35-40).

- Forgiveness and Mercy: Jesus emphasized forgiveness and mercy over strict punishment (Matthew 18:21-22, Luke 6:37). His teachings suggest that justice is not solely about retribution but includes mercy and the possibility of redemption.

- Challenging Injustice: Jesus frequently challenged social and religious injustices of his time. He criticized the hypocrisy and legalism of religious leaders who burdened people but did not help them (Matthew 23:1-4).

- Inner Righteousness: He taught that true justice and righteousness are matters of the heart, not just external compliance with the law (Matthew 5:20-22). This speaks to the importance of intentions and attitudes in matters of justice.

- The Parable of the Good Samaritan: In this parable (Luke 10:25-37), Jesus defines a neighbor as anyone who is in need, and he demonstrates that showing mercy is a key component of justice. The parable breaks down ethnic and religious barriers, highlighting the universality of justice.

- The Beatitudes: In the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:3-12), Jesus pronounces blessings on those who are poor, meek, merciful, and who hunger for righteousness, thus emphasizing that God’s vision of justice often contrasts with human power dynamics.

In essence, Jesus’ definition of justice is characterized by love, compassion, mercy, and a deep concern for the welfare of all people, especially the less privileged and those treated unjustly.

His teachings encourage a holistic approach to justice that cares for the physical, social, and spiritual needs of individuals and communities.

What Is A Right?

A “right” is a fundamental principle or entitlement that is considered justifiably belonging to every person.

Rights are often considered inherent to the dignity and well-being of individuals and are typically protected and upheld within legal and social systems.

There are several key aspects to understand about rights:

- Human Rights: These are the basic rights and freedoms that belong to every person in the world, from birth until death. They apply regardless of where you are from, what you believe, or how you choose to live your life. These universal rights are often expressed and guaranteed by law, in the forms of treaties, customary international law, general principles, and other sources of international law. Human rights include the right to life, freedom of expression, equality before the law, and the right to be free from arbitrary detention.

- Civil Rights: These are the rights of citizens to political and social freedom and equality. Civil rights include the right to vote, the right to a fair trial, the right to government services, and the right to public education. Civil rights are protected by law and are intended to ensure the full participation of individuals in a nation’s political and civic life.

- Legal Rights: These are rights granted by the legal system of a particular state, enforceable by the law. They can vary greatly from country to country and may include rights such as property rights, privacy rights, and contractual rights.

- Natural Rights: These are rights that are considered inherent and inalienable, not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government. The concept of natural rights is closely related to the idea of natural law, and it was a key element in the development of modern human rights. It includes the belief that individuals have basic rights such as the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- Moral Rights: These are rights that are based on ethical principles or moral norms. They may or may not be codified into law. Examples include the right to be treated with dignity and respect or the right to have one’s moral choices respected.

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights: These rights relate to the conditions necessary to meet basic human needs and include rights such as the right to work, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living.

Rights are often interdependent and can sometimes be in tension with one another.

Balancing these rights in a way that respects and protects the rights of all individuals is a key challenge for legal and social systems.

The concept of rights is central to social justice, politics, law, and ethics, serving as a framework for governing individual behavior and the relationships between individuals and society.

Where Do Rights Come From?

The origin of rights is a subject of considerable philosophical, legal, and political debate.

Different theories and belief systems offer various explanations for where rights come from:

- Natural Rights Theory: This theory posits that rights are inherent to human beings and are not granted by any external authority. Natural rights are often thought to be universal and inalienable, meaning they cannot be rightfully taken away. This perspective was famously articulated by philosophers like John Locke, who argued that certain rights such as life, liberty, and property are natural and self-evident.

- Legal Positivism: In contrast to natural rights, legal positivism holds that rights are created by and derive from laws enacted by governments. According to this view, rights exist because they are recognized and protected by a legal system. What is considered a right in one society may not be recognized as such in another, depending on its laws and legal traditions.

- Divine Theory: Some believe that rights are granted by a divine entity or through religious teachings. In this view, rights are understood as part of a moral order that is grounded in religious beliefs and teachings.

- Social Contract Theory: This theory suggests that rights arise from social contracts or agreements among individuals in a society. Philosophers like Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that people agree, either explicitly or implicitly, to form societies and establish governance structures that define and protect rights.

- Utilitarianism: From a utilitarian perspective, rights are a construct designed to promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Here, rights are not seen as inherent but as tools for creating societal happiness and well-being.

- Cultural Relativism: This viewpoint suggests that rights are not universal but are instead a product of specific cultural contexts. What is considered a right in one culture may not be recognized in another, with rights being understood and defined differently across societies.

- Historical Development: Some argue that rights evolve over time, emerging from historical processes, struggles, and societal changes. The development of democratic institutions, for example, has been crucial in the recognition and protection of certain rights.

- Human Rights Conventions and Declarations: In the contemporary international context, many rights are defined and agreed upon through international conventions and declarations, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These rights are then adopted into national laws and practices.

The origin of rights is a topic with diverse perspectives and interpretations, ranging from inherent natural rights to rights as constructs of law, society, or culture.

The understanding of where rights come from can significantly influence how they are recognized, protected, and enforced in different societies.

What Do You Have The Right To Do?

The rights individuals generally have, these can vary significantly depending on the country and its legal system.

In many democratic societies, there are common rights that are widely recognized, often enshrined in law or constitution.

These include:

- Right to Life: The fundamental right to life is the cornerstone of most human rights frameworks. It is the right to not have one’s life arbitrarily taken away.

- Freedom of Speech and Expression: Many democratic countries recognize the right to freely express one’s opinions and ideas, subject to certain limitations like hate speech laws or libel laws.

- Right to Privacy: The right to privacy is increasingly recognized as important, especially in the digital age. It includes the right to have personal information protected and not to be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with one’s privacy.

- Freedom of Religion and Belief: This is the right to practice, change, or renounce a religion or belief, and to manifest one’s religion or beliefs in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.

- Right to a Fair Trial and Due Process: Individuals have the right to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, and to due process in any legal proceedings.

- Right to Education: The right to education is recognized in many countries, providing for access to basic education and sometimes higher education.

- Freedom of Assembly and Association: This includes the right to peacefully assemble, protest, and associate with others, including the right to form and join trade unions.

- Right to Vote and Participate in Government: In democratic societies, citizens generally have the right to vote in elections, run for public office, and participate in government affairs.

- Rights in the Workplace: This includes rights such as fair wages, safe working conditions, and the freedom from discrimination in employment.

- Freedom from Discrimination: Protection against discrimination based on race, gender, religion, nationality, disability, sexual orientation, or other status.

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights: These include a range of rights related to an adequate standard of living, including the rights to health, housing, and food.

It’s important to note that while these rights are widely recognized in many countries, their implementation and enforcement can vary greatly.

Additionally, international human rights treaties and conventions also set forth a variety of rights, which nations may choose to adopt or ratify.

What Do You ‘Not’ Have The Right To Do?

While the scope of individual rights can vary depending on the jurisdiction and legal system, there are certain actions and behaviors that are generally not considered rights and are typically prohibited or restricted by law.

These limitations are often in place to protect the rights, safety, and well-being of others, as well as to maintain public order and decency.

Some common examples include:

- Infringing on Others’ Rights: You do not have the right to take actions that unjustly infringe on the rights of others. For example, your freedom of speech does not include the right to incite violence or engage in hate speech.

- Committing Crimes: Individuals do not have the right to engage in activities that are defined as criminal by law, such as theft, assault, murder, or fraud.

- Endangering Public Safety: Actions that endanger the safety of others, such as reckless driving or creating hazardous situations, are not protected under individual rights.

- Discrimination: You do not have the right to discriminate against others based on characteristics such as race, gender, religion, or sexual orientation, especially in contexts such as employment, housing, and access to services.

- Violating Intellectual Property Rights: Copying or using someone else’s intellectual property without permission, such as pirating movies or music, infringes on their rights and is not a lawful activity.

- Defamation: Making false statements that harm the reputation of another person (libel or slander) is not protected and can be subject to legal action.

- Trespassing: Entering someone else’s property without permission is generally not a right and can be subject to legal penalties.

- Interfering with Others’ Privacy: Violating someone’s privacy, whether through unauthorized surveillance, hacking into personal accounts, or other means, is not a protected right.

- Resisting Lawful Arrest: While individuals have rights regarding fair treatment by law enforcement, actively resisting lawful arrest is typically not a protected action.

- Child Exploitation: Any form of child abuse, exploitation, or actions that harm minors are not rights and are strictly prohibited by law.

These restrictions are generally in place to balance individual freedoms with the rights and safety of others and the interests of society as a whole.

It’s important to understand that rights often come with responsibilities and limitations, especially when exercising one’s rights could impact the rights and well-being of others.

What Is Truth?

“Truth” is a concept that has been explored and debated extensively in philosophy, religion, and science, and its definition can vary depending on the context and the philosophical or theoretical perspective.

Broadly speaking, truth is generally considered to be the state or quality of being in accord with fact or reality. Here are some key perspectives on the nature of truth:

- Correspondence Theory: This is a common perspective in the philosophy of truth. According to this theory, a statement or belief is true if it corresponds to or accurately represents reality. For example, the statement “snow is white” is true if snow is indeed white.

- Coherence Theory: This theory posits that truth is determined by the degree to which a concept or statement coherently fits within an existing system of beliefs or knowledge. In this view, truth is more about consistency within a given framework than about correspondence to external reality.

- Pragmatic Theory: From the pragmatic perspective, a statement is true if it proves useful or effective in practical application. The truth is thus evaluated based on the outcomes of believing or acting upon a statement.

- Constructivist Theory: In this view, truth is seen as constructed by social processes, historically and culturally specific, and is therefore not absolute. What is considered true in one culture or context might not be seen as true in another.

- Religious or Spiritual Perspectives: Many religions and spiritual beliefs have their own conceptions of truth, often tied to divine or spiritual knowledge, moral truths, or ultimate realities beyond the physical world.

- Scientific Truth: In science, truth is often associated with facts, theories, and laws that are based on empirical evidence and logical reasoning. Scientific truths are always open to revision and refinement in the light of new evidence.

- Subjective Truth: This concept acknowledges that some aspects of truth can be personal and individual, based on one’s own experiences, perceptions, and feelings.

- Objective Truth: Objective truths are those that are believed to exist independently of individual thoughts and perceptions, often associated with physical, observable realities.

In everyday use, truth is often understood as accuracy in description or representation, reliability in information, and sincerity in expression.

The philosophical exploration of truth delves deeper into how we determine what is true, the nature of truth itself, and the relationship between truth, belief, and knowledge.

How Do You Know It’s The Truth?

Determining whether something is true can be complex, and the methods used to establish truth depend on the context and the nature of the claim.

Here are some key approaches and criteria commonly used to assess truth:

- Empirical Evidence: This involves using observable, measurable evidence to support a claim. In scientific inquiry, for example, a hypothesis is tested through experiments and observations. If the evidence consistently supports the hypothesis, it is considered true until proven otherwise.

- Logical Consistency: A statement or theory should be logically consistent and coherent. It shouldn’t contain contradictions or inconsistencies. Logical analysis is used in mathematics, philosophy, and other disciplines to determine truth.

- Corroboration and Peer Review: In many fields, especially in science and academia, the validity of a claim is strengthened through corroboration by independent sources or peer review. This process involves experts evaluating the methodology, data, and conclusions of a study or claim.

- Reproducibility: If a result can be reliably reproduced by others following the same method, it adds to the credibility of the original finding. This is a fundamental principle in scientific research.

- Reliability of Sources: The credibility of the sources providing information is crucial. Reliable sources are typically those with expertise, a track record of accuracy, and no clear biases that might distort their reporting of facts.

- Historical/Documentary Evidence: In historical research, the truth of a claim is often established through analysis of historical documents, archaeological evidence, and other primary sources.

- Consensus Among Experts: While not an infallible guide, widespread agreement among qualified experts can be a strong indicator of truth, particularly in complex fields where laypeople may not have the expertise to make informed judgments.

- Pragmatic Test: Sometimes, a claim is considered true if it works or resolves a problem effectively. This is more common in applied fields like engineering or in everyday problem-solving.

- Personal Experience: While subjective and potentially fallible, personal experience can be a source of truth, particularly in matters of personal belief or preference.

- Intuition and Faith: In some areas of belief, particularly in religion or personal values, truth is often accepted on the basis of faith or intuition. While not verifiable in the same way as empirical claims, these truths are deeply meaningful for many people.

It’s important to recognize that different domains (science, law, philosophy, personal belief) have different standards for establishing truth.

Moreover, our understanding of what is true can change over time with new information and insights.

The pursuit of truth is often an ongoing process rather than a final, unchangeable state.

What Is Heart?

The term “heart” has both literal and metaphorical meanings, each significant in its own context:

Literal Meaning: The Organ

- Biological Function: In the literal, biological sense, the heart is a vital organ in the body responsible for pumping blood through the circulatory system. This blood circulation delivers oxygen and nutrients to body tissues and removes carbon dioxide and other wastes.

- Structure: The human heart is a muscular organ roughly the size of a fist, located slightly to the left of the center of the chest. It is divided into four chambers: two atria (upper chambers) and two ventricles (lower chambers).

- Cardiovascular System: The heart works as part of the cardiovascular system, which includes the heart, blood, and blood vessels. It plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis, a stable internal environment in the body.

- Health and Disease: Heart health is central to overall health and well-being. Conditions such as heart disease, heart attacks, arrhythmias, and heart failure are significant medical concerns and areas of extensive medical research.

Metaphorical or Symbolic Meaning

- Emotions and Feelings: Metaphorically, the heart is often described as the center of human emotions, especially love, compassion, and affection. Phrases like “heartfelt” or “broken heart” illustrate this usage.

- Moral or Spiritual Center: The heart is sometimes used to denote the core of a person’s moral or spiritual being. It can symbolize one’s innermost character, values, or conscience.

- Courage and Resolve: In certain contexts, “having heart” means to have courage, determination, or inner strength.

- Cultural Symbolism: The heart symbol (♥) is widely recognized as a symbol of love and is used extensively in art, literature, and iconography.

- Art and Literature: In art and literature, the heart often represents deep, personal, and ineffable aspects of human experience, from profound love to existential suffering.

The heart has both a critical physiological role as an organ in the human body and a rich symbolic significance in various cultural, emotional, and spiritual contexts.

How Does Scripture Define Heart?

In scripture, particularly in the context of the Bible (both the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and the New Testament), the term “heart” is often used metaphorically and carries a profound and multifaceted significance.

It’s important to note that the biblical concept of the heart is quite different from the modern view, which primarily associates the heart with emotions, especially romantic love. In biblical times, the heart was thought to be the center of a person’s being, encompassing mind, soul, and spirit.

Here are some key aspects of how the heart is defined and understood in scripture:

- Center of Thought and Reason: Unlike the contemporary view that associates thought and reason with the brain, ancient Hebrew culture considered the heart as the center of intellect and wisdom. For example, Proverbs 2:10 says, “For wisdom will enter your heart, and knowledge will be pleasant to your soul.”

- Seat of Emotions and Desires: The heart in scripture is often associated with a wide range of emotions, including joy, sorrow, love, fear, and hatred. It is viewed as the wellspring of desires and passions.

- Moral and Spiritual Core: The heart is seen as the source of moral integrity and spiritual life. It is the place where one discerns right from wrong and is the seat of conscience. Scriptures often speak of the need for a “pure heart” or a “clean heart.”

- Relationship with God: In many biblical passages, the heart signifies a person’s relationship with God. A “heart after God” or a “hardened heart” reflect one’s openness or resistance to God’s will and presence. For example, in the Psalms, David frequently prays for a pure heart or expresses his desire to seek God with his whole heart.

- Innermost Being: The heart represents the true nature of a person, their authentic self, beyond external appearances. It’s about the inner thoughts, intentions, and motivations. Jesus emphasized this when he taught that what comes out of a person’s heart is what defiles them (Mark 7:15).

- Transformation and Renewal: The idea of a new heart or a heart transformed is a key theme in both the Old and New Testaments, symbolizing spiritual renewal and a change in one’s life orientation. For instance, Ezekiel 36:26 says, “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.”

In scripture, the heart is much more than just the seat of emotions.

It encompasses the intellectual, moral, spiritual, and emotional aspects of a person. It is the core of who they are and the place where their relationship with the divine is cultivated and experienced.

What’s Bob Proctor’s Explanation Of Heart?

Bob Proctor, a renowned author, speaker, and personal development coach, is best known for his work in the field of success and the power of the mind.

His explanation of the concept of “heart” often intertwines with his teachings on mindset, the law of attraction, and personal potential.

Proctor’s perspective on the heart can be summarized in a few key points:

- Emotional Mind: Proctor often describes the heart as symbolic of the emotional mind or the subconscious mind. In his view, the heart represents the part of our mind that is deeply connected to our true feelings and desires. It’s not just about emotions in a traditional sense but about the deeper inclinations and motivations that drive our behavior and choices.

- Alignment with the Mind: He emphasizes the importance of aligning one’s heart (emotions and desires) with one’s mind (thoughts and rational plans). Proctor suggests that true success and fulfillment come when there is harmony between our deepest desires and our conscious goals and thoughts.

- Inner Guidance: Proctor often speaks of the heart in the context of intuition or inner guidance. He suggests that the heart can guide us towards our true purpose and help us make decisions that are aligned with our deeper selves.

- The Law of Attraction: In line with his teachings on the law of attraction, Proctor believes that the heart, or our emotional state, plays a crucial role in attracting circumstances into our lives. Positive emotions and a heartfelt belief in one’s goals are seen as key to manifesting desires.

- Barrier to Success: He also talks about the heart in terms of personal barriers or limiting beliefs held in the subconscious mind. He believes that transforming our deep-seated beliefs and fears is essential for achieving success and happiness.

- Visualization and Feeling: Proctor emphasizes the power of visualization combined with the feeling – urging individuals to not only picture their goals but to emotionally connect with them as if they were already achieved. This process, he believes, engages the heart and activates its power in the law of attraction.

In essence, Bob Proctor’s view of the heart is less about the physical organ and more about the emotional and subconscious aspects of the human mind.

He focuses on how understanding and aligning one’s emotional self (heart) with one’s conscious intentions (mind) is key to personal and professional success.

How Do You Deal With Someone Who’s Not Interested In The Truth?

Dealing with someone who is not interested in the truth can be challenging, especially if the truth is important for the situation or relationship. Here are some strategies that might help in such situations:

- Understand Their Perspective: Try to understand why they might be resistant to the truth. Are they afraid, in denial, or do they have some other underlying reason? Understanding their perspective can guide your approach.

- Build Trust: People are more likely to be open to the truth from someone they trust. Focus on building a relationship of trust and respect. Be patient, as this can take time.

- Communicate Clearly and Respectfully: Present information in a clear, concise, and non-confrontational manner. Avoid accusatory or judgmental language, as it can make people defensive.

- Use Empathy: Show empathy and compassion. Acknowledge that accepting the truth can sometimes be difficult or painful.

- Provide Evidence: If appropriate, provide factual and objective evidence to support the truth. Sometimes, visual or tangible proof can be more persuasive than words alone.

- Pick Your Battles: Consider whether insisting on acceptance of the truth is necessary in the situation. Sometimes, it may be more prudent to focus on more critical issues or to let go if the matter is not of high importance.

- Encourage Critical Thinking: Encourage them to think critically and question things. This can help them to see the value of seeking truth themselves.

- Set Boundaries: If their denial of the truth is harmful or toxic, set clear boundaries. Protect your well-being and make it clear that certain behaviors or falsehoods are unacceptable.

- Seek Mediation or Professional Help: In some cases, especially where important decisions or relationships are at stake, seeking help from a neutral third party or professional (like a mediator or counselor) can be beneficial.

- Accept Their Autonomy: Ultimately, you can’t force someone to accept the truth. People have the autonomy to choose their beliefs and actions. You may need to accept that they might not be ready or willing to face the truth, at least for now.

- Reflect on Your Approach: Consider whether your approach might be contributing to their resistance. Sometimes, a different communication style or strategy can be more effective.

- Focus on Your Reaction: You have control over your reactions and actions. Maintain your integrity and stay true to your understanding of the truth, regardless of how others respond.

Dealing with someone who is resistant to the truth requires a balance of empathy, clear communication, and sometimes, accepting that you have done what you can and it is up to them to come to terms with the truth in their own time and way.

Is The U.S. Court System A Reasonable Way For Dealing With Those Who Are Not Interested In The Truth?

The U.S. court system is designed to handle disputes and legal matters through a structured legal process, and it has mechanisms in place to deal with individuals who may not be interested in the truth.

Whether it is a “reasonable” way depends on the context of the situation and the expectations of the legal system.

Here are some aspects to consider:

- Fact-Finding Process: Courts are equipped with a rigorous fact-finding process. Through the presentation of evidence, witness testimony, and legal arguments, courts aim to ascertain the facts of a case.

- Legal Representation: Both parties in a dispute have the right to legal representation. Lawyers play a crucial role in presenting evidence and arguments to support their clients’ positions and in challenging the veracity of the opposing party’s claims.

- Rules of Evidence: The court system operates under strict rules of evidence that determine what information can be presented in court. These rules help ensure that the evidence is relevant, reliable, and not overly prejudicial.

- Cross-Examination: This is a key feature of the adversarial system used in U.S. courts, allowing for the challenging of testimony and claims presented by the other side. It is a tool to test the credibility of witnesses and the strength of the opposing party’s case.

- Judicial Oversight: Judges oversee the legal process to ensure that it is fair and just. They have the authority to rule on the admissibility of evidence and to provide instructions to juries on how to interpret and apply the law.

- Jury System: In many cases, a jury of peers is responsible for determining the truth based on the evidence presented. The jury system is designed to reflect a cross-section of the community, bringing diverse perspectives to the judgment process.

- Perjury Penalties: The court system treats truthfulness very seriously. Witnesses are under oath, and lying under oath is a criminal offense (perjury), which can result in significant penalties.

- Appeal Process: If a party believes that the outcome of a trial was unfair or that there were legal errors, they can appeal to a higher court, which provides another level of review.

- Limitations: Despite these mechanisms, the legal system is not infallible. Complex cases, issues of interpretation, the skill of legal representation, and other factors can influence outcomes. Sometimes, the truth may be elusive or open to different interpretations.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): For some disputes, especially where parties may not agree on the truth or facts, alternative methods like mediation or arbitration can be more appropriate. These methods are often less adversarial and can be more focused on finding a mutually acceptable resolution.

The U.S. court system is structured to deal with issues of truth and falsity in a formal, legalistic manner. It provides a framework for resolving disputes based on evidence and legal principles.

While it is a reasonable avenue for many legal issues, it may not be the most suitable or effective method in every situation, particularly where the parties might benefit from a less adversarial approach.